Before our recent staffing changes, this time of year our work emails begin pinging with last minute attempts to get the upcoming Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year holidays off of work. Under most circumstances, staffing issues aside, it is a pretty easy process to get a day off work. However, during the holidays, it is a completely different story. In order to get a holiday off of work, there’s usually an added price associated with your standard trade off request. People want to be with their families on the holiday, and when the typical email of “hey can anyone work my shift?” is met with crickets, a bonus amount of cash is usually thrown into the equation to get your shift covered. I did a bit of digging into my email archives to gather some data points on prices of getting work off to be with your family on the holidays. It’s very much back of the napkin analysis, but I think it illustrates the concept of supply and demand in determining price quite well.

Before I get into the economics, I want to go on record to say I’ve never really liked this holiday bidding process, but I understand why it is here to stay, especially in these tough times. I appreciate that in our department, we have a strong expectation that newer members work holidays so that senior firefighters who have paid their dues and most likely have started families later in their career can take the time off to be with them. I just don’t think I’ll ever feel like I’m that deserving person and I’ll just instead work on my assigned holidays. Besides, working on the holidays has always been fun. Perhaps I have my childhood to thank for having such a lax view on all this.

You see, I grew up with a father in the fire service. As a kid, I knew my father worked 1/3 of the year at the fire station. Some years he would have the holidays off and other years, we would spend the holidays at his fire station. As a young child, I cherished the times spent at the fire station. I’d get to play on the fire engine and hang out with the kids of the other firefighters. The men and women in uniform at my dad’s station were like a second family to me and they welcomed us with open arms into their home away from home. Inevitably, the crew would get a call in the middle of cooking and all of the family would watch the engine take off to go help someone in need. I always thought it was so cool! As a father to two small children, I hope my kids have the same feeling of warmth and belonging from our fire department and will do everything in my power to continue this tradition.

In doing the research for this article, I was amazingly humbled and proud of my department. Often times the cash offered was never accepted by the person working the holiday, a testament to our enduring camaraderie. For as many emails that I looked for with cash incentives, there were twice as many more of people offering to come in to work Christmas morning or evening so that our members could at least spend part of the day at home with their loves ones. Our Chiefs have sent emails every year thanking those that had to work on the holidays. Some years they even visited the stations to thank us in person. Seriously humbling and awe inspiring! Now back to the economics…

What Determines A Price?

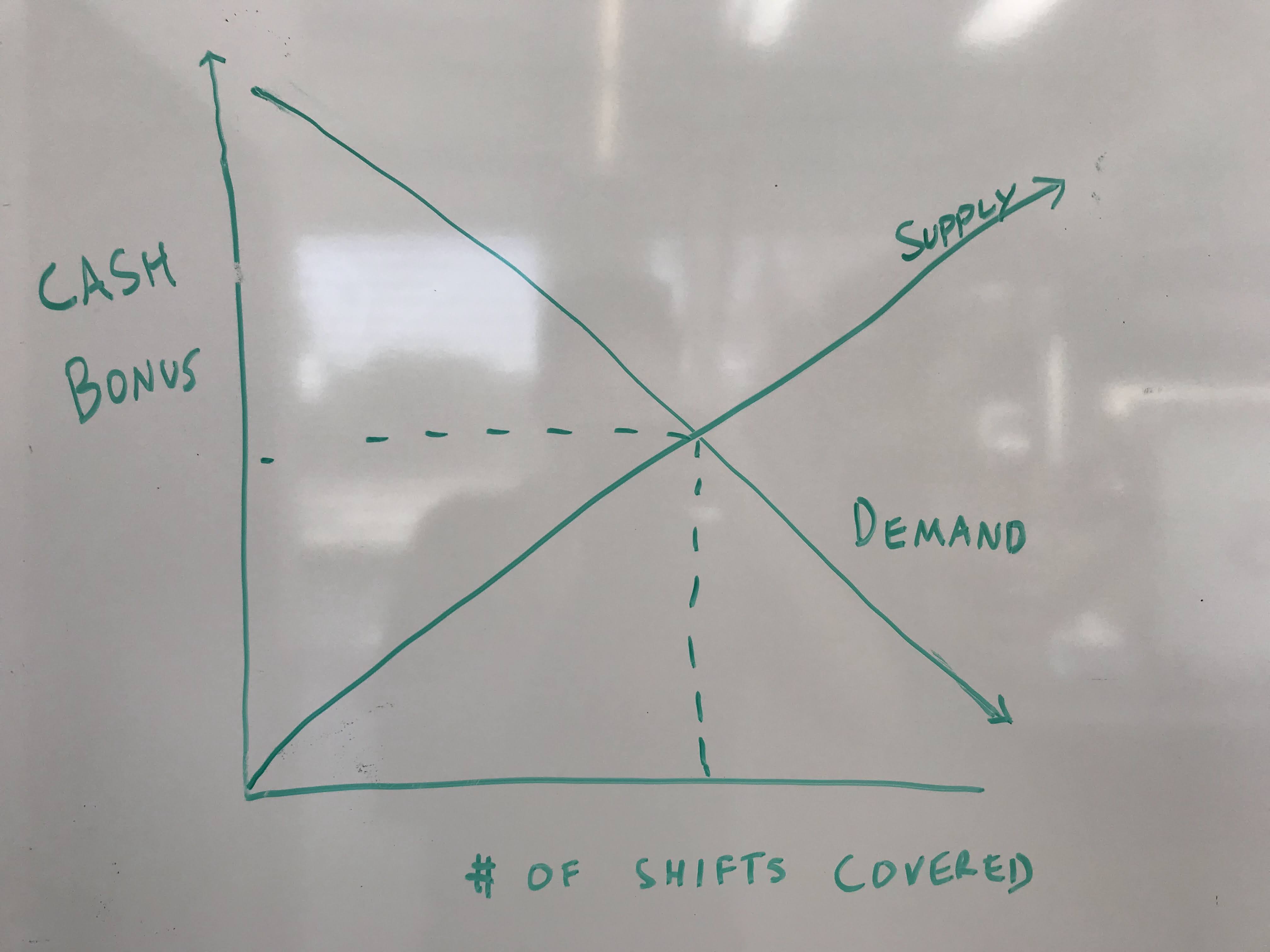

A price of something isn’t just an arbitrary number pulled from thin air, it is a function of supply and demand pressures. If you can understand the forces that drive supply and demand for a given product or service, you can more accurately determine a correct price. A price is the ultimate communicator to a producer looking to make money, and a consumer looking to buy a product or service. While there are an infinite amount of factors to consider, we will keep it simple and opt to dissect each in subsequent articles. The bottom line is someone is willing to produce or offer a service (producer) and someone is willing to buy this good or service (consumer) only when the price is agreeable for both parties. Get the price wrong and either the producer or the consumer is loosing out big time. If left to their own devices, over time, the market finds the perfect price. This is often referred to as equilibrium. Onto supply and demand.

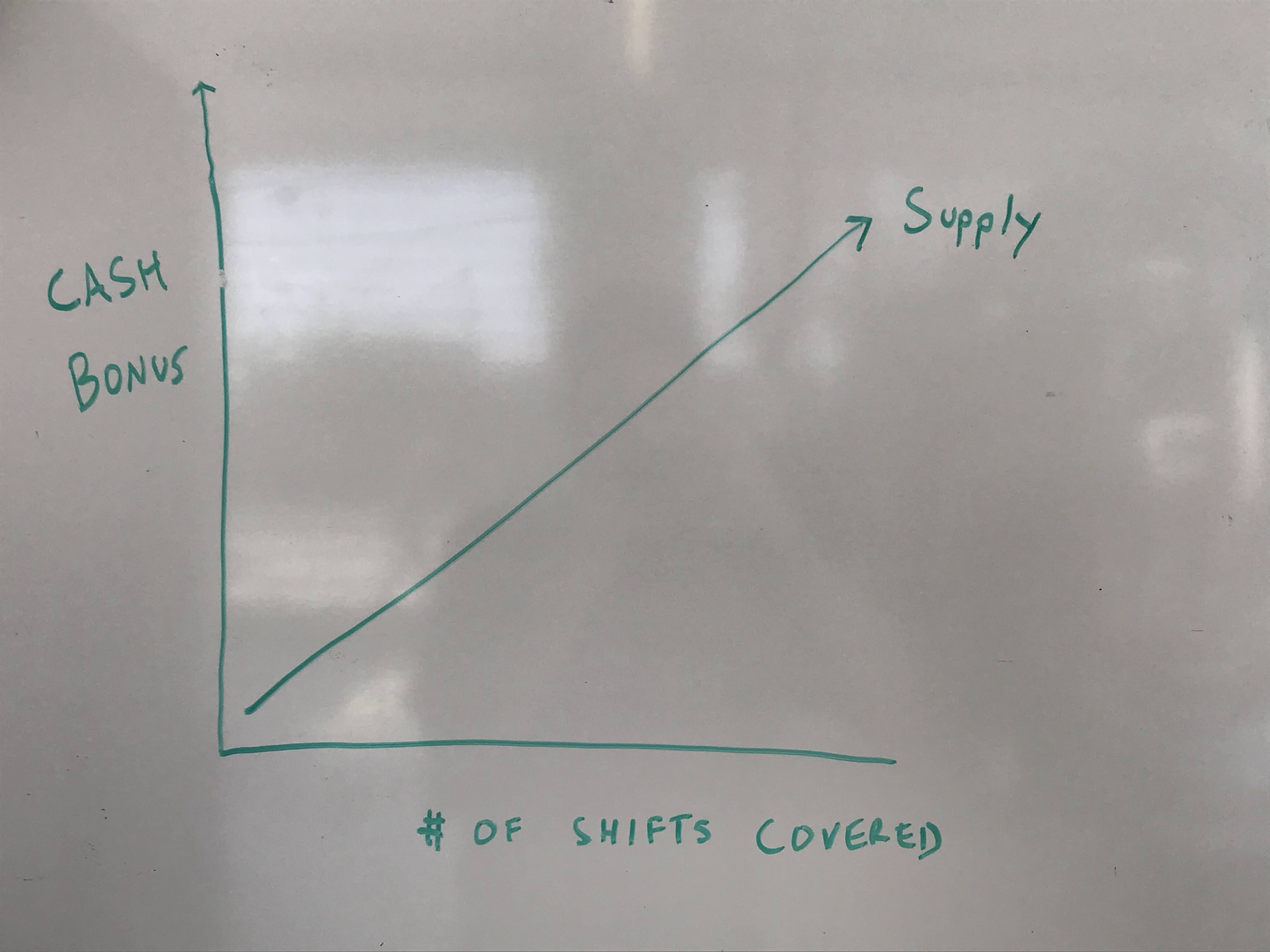

Supply

If you are a producer of a good or offering a service, your time and energy inputs into providing have a cost. If you are a fire engine manufacturer, your costs would be labor, raw materials and other business expenses. You will only produce if you can cover your costs and you will produce a lot more if the price you get for your good or service increases beyond your initial costs. If you are a firefighter considering working on the holidays, the cost is quite simply the missed opportunity of being with your own family on the holiday. Obviously this cost isn’t the same for everyone in our ranks. Some people have kids that love their parents home for Christmas morning. Some people are single and have no family in town. For the average firefighter however, there are bills to be paid, and if you keep raising the price of a holiday bonus, you will be apt to find more and more firefighters willing to work the shift for you. For simplicity sake, we will assume every firefighter has a uniform price point that works for them. If graphed out, with the horizontal axis being the number of people available to work a holiday shift and the vertical axis being the bonus paid to work a shift, you ought to see a steady rise upwards moving from left to right. The higher the bonus, the more people will want to work.

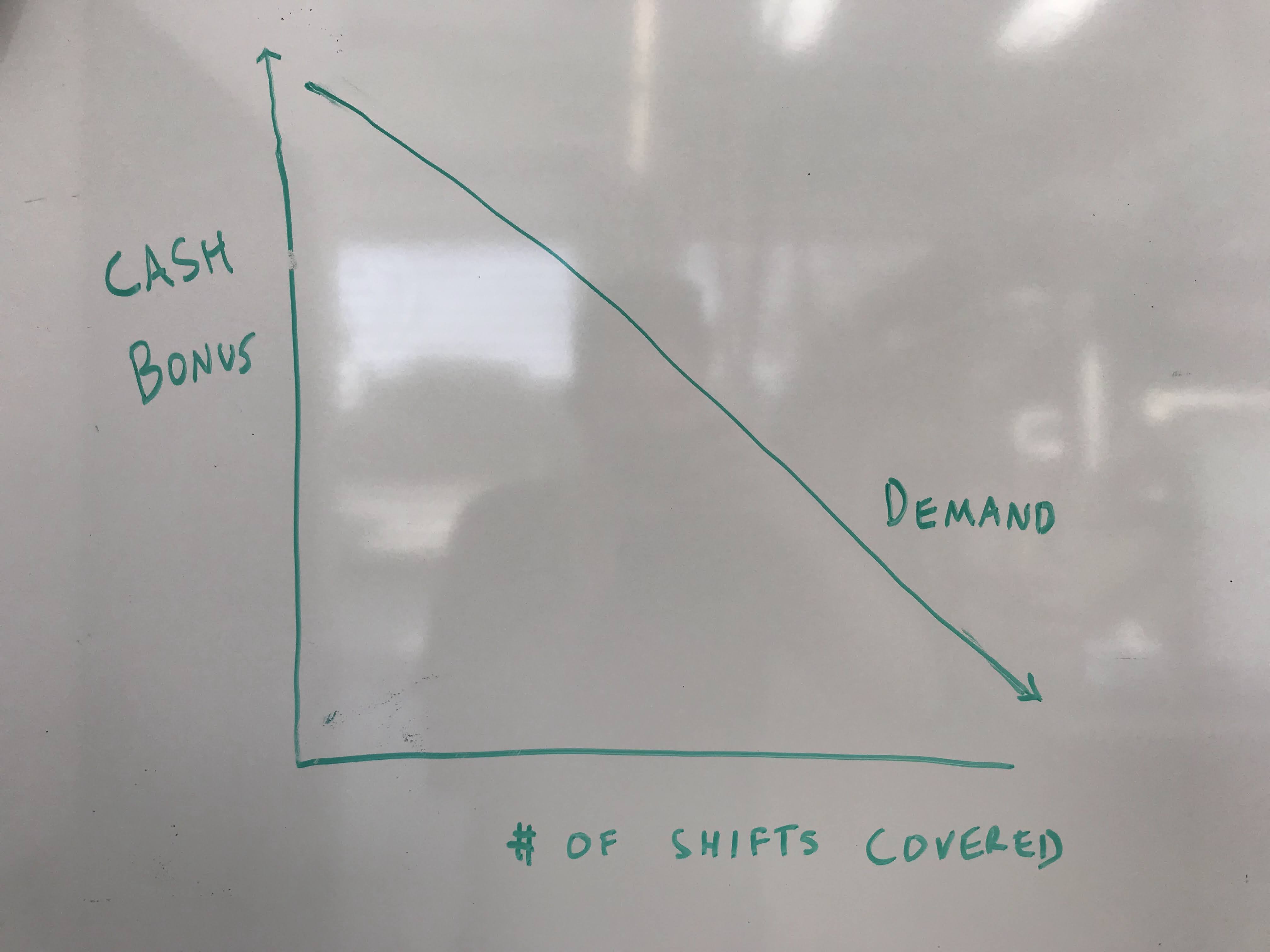

Demand

If you are a consumer, you are the person looking to buy a given product or service. The money you spend for this good and service is in competition with other goods and services that you may want or need, therefore you are sensitive to the price. Therefore, the higher the price, the less likely you are to pay for the good and service. If you are a firefighter looking to pay someone extra to get the holiday off, you will be more apt to spend the money if the cost is lower. If graphed out, with the horizontal axis being the number of people available to work a holiday shift and the vertical axis being the bonus paid to work a shift, you ought to see a steady decline downward moving from left to right.

Price Is In The Equilibrium

From these two functions, representing the supply side of a transaction and the demand or consumer side of the equation, you see a nice clean intersection of supply and demand. At the intersected points of the supply and demand curve, you find your perfect price for a good and service. At this price, both the buyer and seller are satisfied with their transaction.

An Experiment

The trickle of holiday emails have begun to flow as Halloween is over and I was quite shocked at the inflated price for getting Christmas or Christmas Eve off of work. This is a simple analysis, but I dug through my email archive, which dated back to 2017 with the simple search of “Christmas.” I tallied up the combined totals of people who offered money to get their shifts covered and reached an average price for each year. Remember supply and demand need to meet in order to reach this price. I made sure to not double count entries. I also only included the final offer, as some people bidded up their total offering to get their shift off (ie $100 to $150 and finally $200 to get their shift off). The averages were as followed for the last few years.

2020- $262 – 12 people offering

2019- $170 -12 people offering

2018- $195.45 – 11 people offering

These are just a few data sets for the rank of captain. In order to conduct a more thorough analysis, you would want to measure all ranks over a longer time frame. I merely wanted to show how changes to supply and demand can affect the price. Let’s use 2019 as our baseline year to compare what supply and demand changes can do to the price of a holiday off with the family.

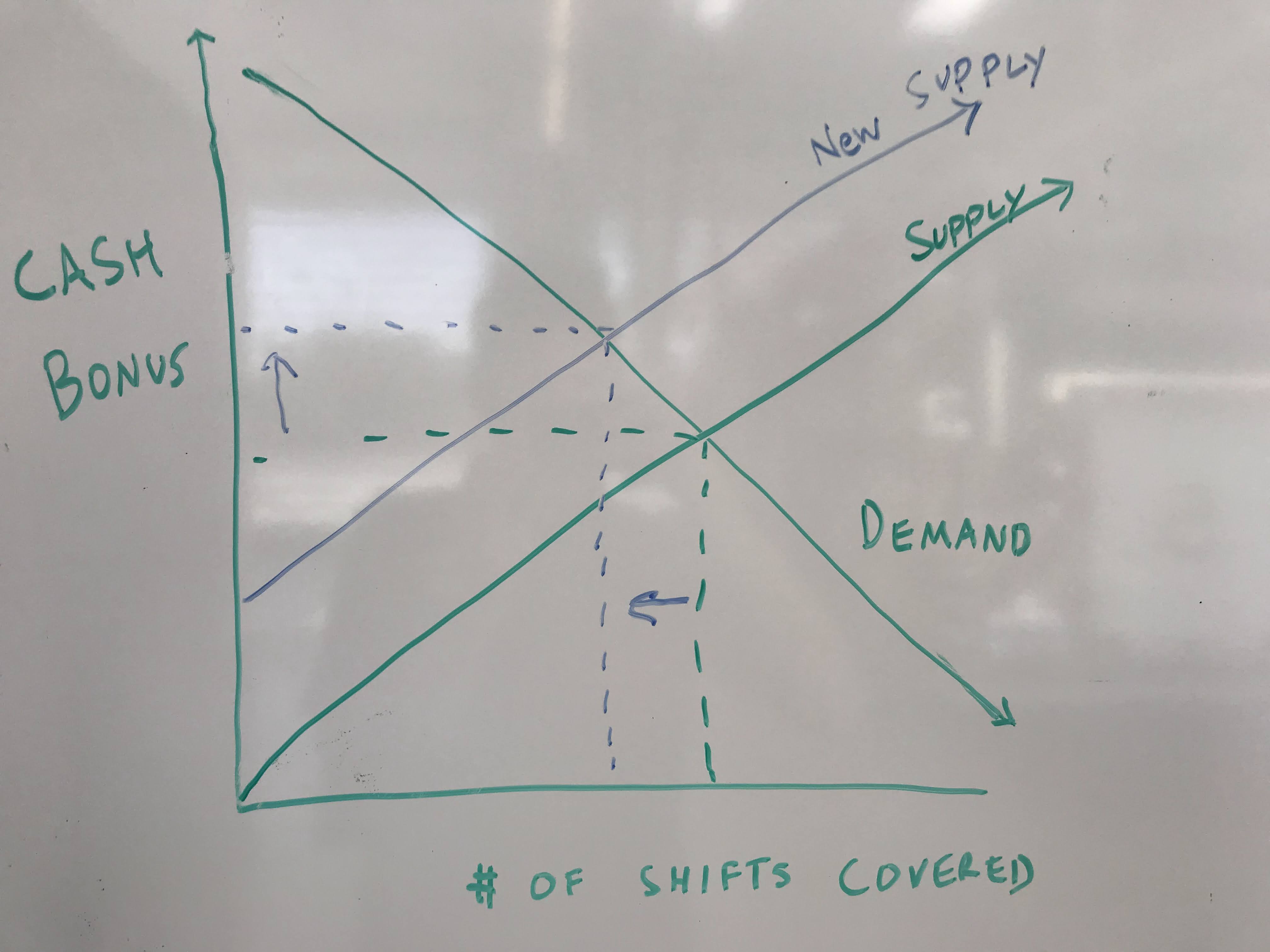

2020: A Supply Shortage?

Note between 2019 and 2020, there was the same amount of demand for shifts being covered, yet a higher price. This could be a sign of a supply shift. 2020 and 2021 have had a lot of mandatory shifts amongst all ranks. I would imagine that this increase in price is due to a shortage of people wanting to work on the holidays. They would rather be at home with their families. This doesn’t insinuate a staffing shortage, but merely a change in supply of people willing to work a holiday. The reasons why are very complex and subject for a wayyyyyyy more in depth analysis. The simple point is to illustrate how a decline in a supply curve could lead to an increased price. The supply curve in this possible scenario would shift to the left, resulting in less people wanting to work but with the same responsiveness to compensation. This would result in a higher price equilibrium and less people getting the day off of work. Same amount of people wanting the day off, yet paying a higher price for it. Again, it’s oversimplified, but it illustrates the concept. Both Supply and Demand curves can shift one way or another.

In Summary

Prices are determined by both Supply and Demand forces. Understanding how markets arrive at a certain price can allow you to make better investment decisions. I have invested a small amount of my portfolio to commodities and have sought to really study supply and demand functions in depth. Recent headlines suggest that supply shortages are causing increases in prices across many different goods and services in many different markets. By investing in sectors that have had lowered supply AND demand due to COVID-19 lock downs, many commodities traders have done well when demand suddenly surges with the economy reopening while supply is slow to respond. It takes longer to open up refineries and factories than it does to suddenly allow for the economy to reopen. Smart commodities traders are capitalizing on this imbalance. I’m doing everything I can to study their trading…back to our example. The example of holiday trades off is one of the best examples of supply and demand functions we deal with as firefighters during the holidays. I hope you and your family have a safe and happy holidays, whether at home or at the fire station.

-TheFirefighterEconomist

One thought on “ALT+ $$$$: Holiday Supply and Demand”